The Essence of the Blues

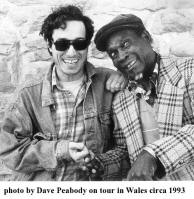

My Brother Michael & David

“Honeyboy” Edwards:

A Friendship For The Ages.

By Allan Dodds Frank

One of the world’s greatest and longest running musical partnerships

ended gently at 3 am Monday August 29 in Chicago when blues guitar

legend David “Honeyboy” Edwards died in his sleep. As the last of

the first generation Mississippi Delta bluesmen, his death closes a

chapter in the history of music. And it meant parting company with

his harmonica player/manager/biographer/record label owner and

closest friend Michael Robert Frank for the last time in their

39-year professional collaboration. Michael and Honeyboy had played

together for more than 38 years in hundreds of bars, auditoriums,

arenas and festivals all over the world.

At 96, Honeyboy was the last Mississippi bluesman alive who had

played with Robert Johnson, the man regarded as the king of the

blues guitar. When Honeyboy was 22, he was in Greenwood,

Mississippi, with Johnson the night he was poisoned and died,

presumably by a jealous husband, according to Honeyboy’s

autobiography “The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing,” which he told to my

brother Michael Robert Frank and co-author Janis Martinson.

At 17, Honeyboy, the son of a sharecropper, began venturing far from

home in Shaw Mississippi as an itinerant bluesman, playing his

guitar for nickels and dimes on the streets of Mississippi,

Tennessee Alabama, Arkansas and Louisiana. Between 1932 and 1956 he

played in 13 states, gambling, working odd jobs, and playing the

blues. He settled down in Chicago in 1956.

In 1972, my brother Michael Frank was just out of college and working as a social worker rescuing abused children when he met Honeyboy at Biddy Mulligan’s, a Northside Chicago bar that featured the blues. Michael, a budding harmonica player, had moved to Chicago from our hometown of Pittsburgh, Pa., to hear and meet blues musicians in local clubs. He considered the elder bluesmen as revolutionaries, during the depression and pre-civil rights era.

Honeyboy, Big Walter Horton, Sunnyland Slim and some of the other

old blues legends in Chicago began teaching Michael how to play,

sharing their stories, and tutoring him in the traditions and

nuances of the blues. Those lessons remained much in evidence when

Michael accompanied Honeyboy as he always complimented and filled in

the sound of the lead guitar player and singer and never played over

him.

Honeyboy, Big Walter Horton, Sunnyland Slim and some of the other

old blues legends in Chicago began teaching Michael how to play,

sharing their stories, and tutoring him in the traditions and

nuances of the blues. Those lessons remained much in evidence when

Michael accompanied Honeyboy as he always complimented and filled in

the sound of the lead guitar player and singer and never played over

him.

The secret, I think, to their relationship was that Michael listened

to Honeyboy and appreciated his wisdom and life experience. Michael

absorbed the music and the stories. As my brother says: “Honeyboy

wasn’t like a father or even a grandfather to me. He was a friend,

business partner, musical partner and we shared plenty of hard times

together over 39 years.”

In his autobiography, Honeyboy details his wariness of white

dominance over the black sharecroppers he came from and the white

enforcement of crushing segregation. If he trusted anybody, it was

Michael and no matter who had an offer or a request, Honeyboy would

say, “Ask my manager.” He was never star-struck, a lesson he also

imparted to Michael.

I know, I was backstage at big shows with Michael and Honeyboy and

it was the big stars who wanted to hang with him. When Martin

Scorsese collected all the living greats at the blues for a historic

concert he filmed at Radio City Music Hall in New York in February,

2003, Honeyboy was the second act – a soloist that night.” Michael

and Honeyboy had to be backstage, so they gave my wife and me their

prime seats near the front. Sitting one row behind us was a star of

the second act, Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, his wife and his

daughter, the model and actress Liv Tyler. As Honeyboy was

playing one of his most classic numbers, “Gamblin' Man,” Tyler was

riveted. He whispered to his daughter: “Imagine how much this old

man knows.”

When Keith Richard appeared unannounced at a small and now defunct

blues club called The Boxcar in Southport, Ct. May 21, 2004 to hear

Honeyboy, he joined Michael and second guitarist Rocky Lawrence on

stage because he wanted to play a number with Honeyboy.

At a House of Blues special tribute to Honeyboy in Boston October 8,

2010 organized by The Reel Blues Fest, Bradford Whiford of

Aerosmith, James Montgomery and three dozen other bluesmen and women

clamored to join Honeyboy on stage and later- in the Blues

Foundation Room. Honeyboy –right down to his memorable venerable

face- oozed the blues just talking to you.

Although Honeyboy was not known for his songwriting and did not

compose many songs, his treatment of the blues classics was

unmatched, whether it was “Goin' Down Slow,” “Pony Blues” or Robert

Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago.” His fingers were lightning fast and

strong. Especially when he played slide guitar, Honeyboy’s sound was

instantly distinctive – penetrating and clear – note-by-note. He was

one of the few slide masters who played in standard tuning.

He liked to talk to his audiences and mix in a little history about

his life on the streets, riding boxcars during the depression and

playing with nearly every name of note in the entire history of the

blues. As Chicago Sun-Times writer David Hoekstra put it: Honeyboy

was the “Shaman of the Blues.”

If you can listen to his albums my brother produced on Earwig Music,

you will understand the loving sense of musical history that went

into making them. Check out Earwig for "Old Friends", “David

Honeyboy Edwards Delta Bluesman,” “Roaming & Rambling,” and “The

World Don’t Owe Me Nothing.”

As a special treat, I booked Michael and Honeyboy to play at my 60th

birthday party on the lawn at our house in Lyme, Ct. To accommodate

me, they performed in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, suburban New York

and New Jersey. Arriving exhausted after a Saturday night gig in

Boston, at age 92, Honeyboy insisted in napping in the car before he

played that Sunday afternoon.

His set was magical, a tour of the blues classics that he began with

a simple admonition. “Now listen up, cause I ain’t playing no dance

music.”